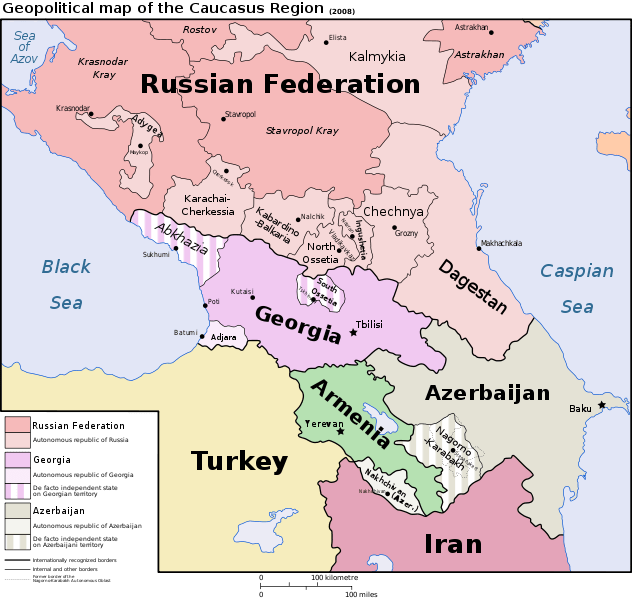

Wikipedia defines South Caucasus (also referred to as Transcaucasia or Transcaucasus) as the southern portion of the Caucasus region between Europe and Asia, extending from the Greater Caucasus to the Turkish and Iranian borders, between the Black and Caspian Seas. All of Armenia is in Transcaucasia; the majority of Georgia and Azerbaijan, including the exclave of Naxçivan, fall within this area.

Wikipedia defines South Caucasus (also referred to as Transcaucasia or Transcaucasus) as the southern portion of the Caucasus region between Europe and Asia, extending from the Greater Caucasus to the Turkish and Iranian borders, between the Black and Caspian Seas. All of Armenia is in Transcaucasia; the majority of Georgia and Azerbaijan, including the exclave of Naxçivan, fall within this area.

Reading a rather boring article on Hetq today about the future of Armenia, I couldn’t help but single out this really interesting paragraph:

Many people speak today about how the South Caucasus is an artificially created region, where the member countries have differing (and sometimes opposing) interests and wishes. Will it unite in the wake of other countries’ entry into the region, or the region’s desire to be part of broader international bodies? Or will it break down as a result of centrifugal forces?

As someone heavily involved in regional media projects over the past 4-5 years I know just how artificial and sometimes challenging it is to try and put the three countries + the bulk of unrecognized countries of this region into one bowl and make sense of it.

We know from history, that the territories described as South Caucasus have been unified as a single political entity twice – during the Russian Civil War (Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic) from 9 April 1918 to 26 May 1918, and under the Soviet rule (Transcaucasian SFSR) from 12 March 1922 to 5 December 1936 (Wikipedia). But as everything artificial, it has twice fallen apart, and I don’t see why and how they could be united again.

Thinking of why this region has come to being a region at all I can only conclude, that as a meeting point between 3 main powers since the 17th century: Russia, Turkey, Iran, this region has acquired a common identity of being a battleground. Today even this reality has changed (although today the region is a battleground of many more interests, including those of Russia, US, UK, Turkey, Iran, British Petrolium, Islam and Christianity…), and looking from a fresh new perspective I don’t see any reason, why these 3 recognized and at least as many unrecognized states should be tied together under the common name.

I hereby state, that we have nothing in common: geographically we are on different continents (Georgia – mostly Europe, Armenia – Asia, Azerbaijan – both Asia and Europe), different ethnicities, different languages, religions, identities, cultures and policies. The world however, continues to refer to us as a common region, perhaps looking at the common history of the people living here, although that history does more to pull us apart, then bring together.

And so we are all stuck together, in this endless marriage of hate and the common label “Faces of Caucasian Nationality”(лица Кавказкой национальности) made by our “big friends” or rather “big enemies” – the Russians.

I would direct your readers to much less theoretical article in the latest issue of Hetq which I found quite depressing. It deals with the plight of Iraqi-Armenians now living in Armenia. THEY WANT TO RETURN!!!!!!!!

Amazing but true!!!!I urge all to read and comment on the plight of these folk who would rather face the vilence in Iraq than reside in Armenia.

I can only believe the difficulties these people mention while living in Armenia. What I can’t understand is why such attempts at repatriation are doomed to failure. When the most despondent and luckless segments of the diaspora find Armenia to be too much to bear, then SOMETHING IS TOTALLY WRONG.

If memory serves me right, hundreds of Jews return to Israel yearly and are provided the necessary services, both psychological and tangible, to make the transfer to a new and alien society that more bearable.

Why can’t the ROA and the Diaspora organize something similar, or is this too much to ask for?????

Chello – thanx for the comment, I will definitely address the issue.

There’s an interesting article here:

http://www.caucaz.com/home_eng/breve_contenu.php?id=287

[…] says that the South Caucasus is an artificial and unnecessary construct — that the three countries within in have little in common. Share […]

I am from Azerbaijan, I had always hated Armenians since my childhood, But our mutual dislike of each other have made our small but beautiful countries puppets of the so-called great powers. Maybe we must reconsider our relations. Maybe the Nagorno Karabakh belongs to both of the countries. In reading the history of Baku, I have surprised when I realised that the city does not belong only us, but also to the Armenians. You are right that the very term ‘South Caucasus’ is artificial. But today, this artificiality is much more real than our differences. Whether like our hate, we share acommon fate. However very few in the South Caucasus region realizes that.

Sabit you are working in OSI?

:))))))

Hey Sabit, no karabaghh does notbelong to “us”, it belongs to Armenians like the land that now belongs to Turkey is not theirs either, it also belongs to Armenians. You need to get on your donkeys and travel back to East where you all came from.